Most Northeast Ohio residents have at least a passing familiarity with Devo, the visually-driven, post-punk brainchild of ŃĹ–‘…ęőÁ“Ļ University School of Art alumni Jerry Casale, Bob Lewis and Mark Mothersbaugh. Perhaps less commonly known is the story of exactly how the band came to be. Devo‚Äôs creation was inspired and catalyzed by the trauma of the May 4, 1970, shooting of student protesters by the National Guard, for which both Casale and Mothersbaugh, (along with fellow former KSU art student/rock luminary Chrissie Hynde) were present. Two of the victims of the violence (Jeffrey Miller and Allison Krause) had been friends of Casale‚Äôs, who later said of the incident,

‚ÄúI had always been making art and music but the events of May 4th and beyond galvanized my creativity, infusing it with an existential anger and urgency that would otherwise not have happened. In short Devo and the idea of De-evolution as a manifesto would not exist without that defining historic trauma I experienced.‚ÄĚ

Casale had started studying 20th-century comparative literature at Kent‚Äôs Honors College in 1966. By 1968, he had added fine arts as a second major, and by May 1970, he and Mothersbaugh had already been individually developing interests in satirical art, fostered by the socio-political climate of the late '60s. The unrest and instability of the time had convinced them that society was regressing or de-evolving - a feeling intensified by the massacre and the public‚Äôs response to it. ‚ÄúThere was certainly a cultural civil war going on (similar to present day) that pitted politically active students who opposed the war in Vietnam against all the pro-war citizens supporting the US Government‚Äôs agenda in southeast Asia,‚ÄĚ says Casale.

‚ÄúIn Kent that meant that the local residents and law enforcement agencies routinely harassed the KSU students who they loathed. That said, nothing that happened on the run up to the May 4th protest against President Nixon‚Äôs expansion of the war into Cambodia without an Act of Congress anticipated the lethal escalation of hostilities that occurred.‚ÄĚ

While the campus was shuttered for six weeks; ‚Äúsealed off with yellow crime-scene tape‚ÄĚ and under martial law in the aftermath of what Casale calls a ‚Äúpoliticized Rite of Spring‚ÄĚ, he, Lewis and, later, Mothersbaugh began a collaboration which has defied categorization and spanned five decades as well as a wide range of media.

‚ÄúArt Devo concentrated on simple, bold, somewhat transgressive imagery designed to elicit either a laugh or scorn (or both). It was art as confrontation. It was a conceptual gun to the head. Then with Mark came the musical experimentation to try to formulate what DEVO music would sound like. That pursuit gained traction and worked well with our multi-media interests. All the visual art inspiration drawing from Americana, print ads, industrial catalogues, outsider art influences, underground films, etc combined in a sort of huge food processor where DEVO, the band became much more than the sum of its parts.‚ÄĚ

That Devo resonated was fortunate for Casale, whose academic career had been derailed by the incident.

The members of Devo did neither - they made art instead. The injustice of the government’s response to dissent in 1970 was a catalyst for them that, once experienced, could not be ignored. Casale credits that time with pushing him to find new ways to express the things that needed to be said:

‚ÄúWhile it‚Äôs hard to find a simple correlation between the life-changing trauma of May 4th 1970 and my post-KSU killings creative work, I can say that the fallout proved to be an aesthetic, as well as political and philosophical, fork in the road - a clear choice to open my eyes and see that history as it had been taught was one big lie. I confronted the vast, illegitimate authority that pervaded American government and institutions of ‚Äėhigher learning‚Äô. My eyes were opened and any illusion that the squeaky-clean idea, the ‚Äėwhite hat‚Äô exceptionalism of the brand known as America had much truth to it was wiped away. I felt like I had unwittingly been complicit in the big lie. The Vietnam War was not an isolated mistake. It was part and parcel of the long history of Imperialist hypocrisy, CIA manipulation, capitalist support of dictatorships, genocide, racism, sexism, etc. Speaking truth to power was everyone‚Äôs responsibility in my view.‚ÄĚ

To achieve this end of speaking truth, Casale and his bandmates utilized not only music and lyrics, but films, costume, performance art like Mothersbaugh‚Äôs ‚ÄúBooji Boy‚ÄĚ and visual media in the form of posters, album covers and the like. Keeping the lyrical component simple so as not to be heavy-handed in their message, Devo embedded meaning into the visuals associated with the band, using them to talk about society, politics and the absurdities of life in the modern age. Along the way they helped usher into the mainstream American consciousness both performance art and punk rock, whose ethos of suspicion of authority is one which Casale still carries, and which is a direct result of his experiences surrounding that ‚Äúbeautiful spring day‚ÄĚ when everything changed forever:

‚ÄúFifty years after the fact the narrative has finally shifted to recognizing the students as victims rather than ‚Äėcommunists‚Äô and ‚Äėtrouble makers‚Äô. That is largely because they now appear to be on the right side of history regarding the USA‚Äôs imperialistic mistake called The Vietnam War. However, in the immediate aftermath of the ŃĹ–‘…ęőÁ“Ļ killings and for at least two decades hence, the official history controlled by right wing media and corporate news sources marched to a different drummer - that of patriotic whitewashing where anti-war sentiment and student activism were portrayed as misguided and downright anti-American. Remember, the parents of the killed and wounded students banded together and brought a class action lawsuit against the University and the State of Ohio. They lost their case on the simple defense argument that invoked the declaration of Martial Law as exonerating them from any liability. Today‚Äôs youth population would do well to read up on how easy it is in a supposedly free society for individual rights to be taken away in a heartbeat.‚ÄĚ

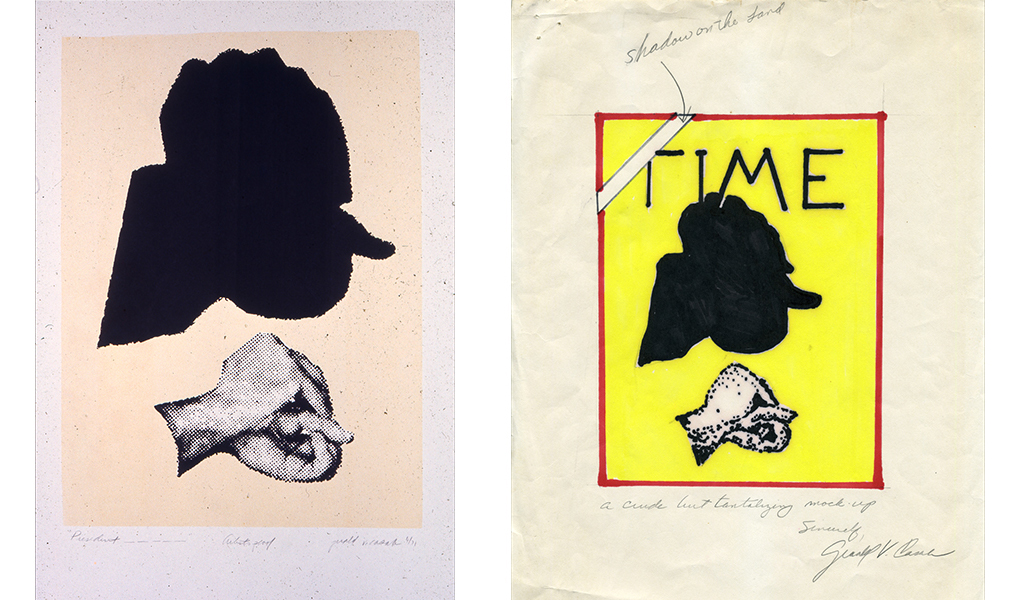

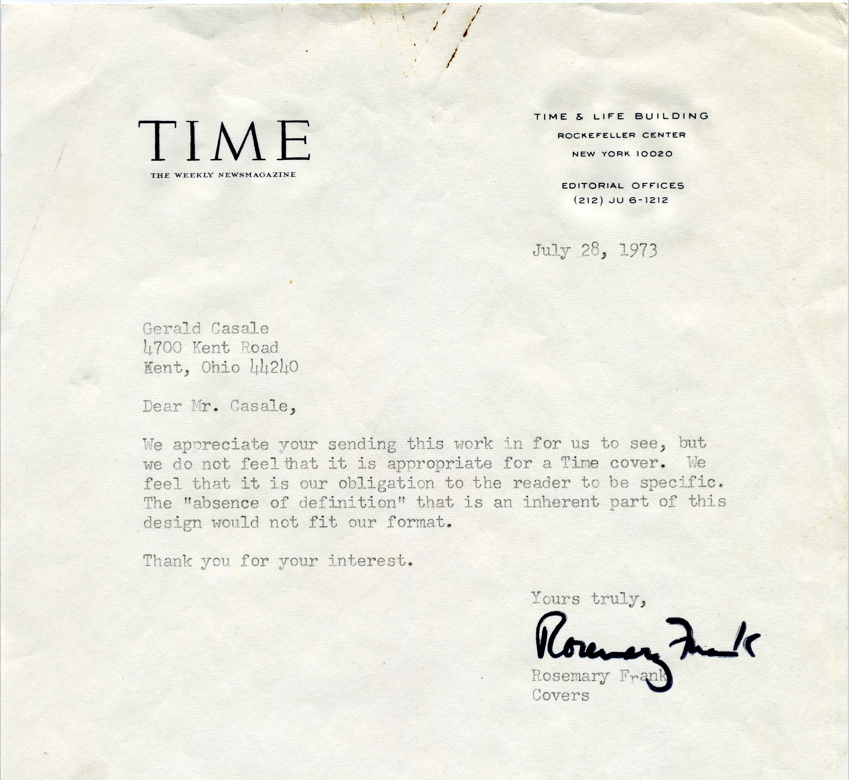

[Image caption: Casale’s student art, fall 1970. A photo-screen called Shadow on the Land “addressing the horrid spectre of Richard Nixon and his path to impeachment." This was submitted to Time magazine for cover art and also pictured is the "inevitable letter of rejection"]

Images courtesy of Gerald Casale.