Cool Tools

Research scientists often have to customize equipment and create laboratories tailored to their needs. With the help of the universityãs machine shops, technicians and their own research teams of postdoctoral associates and students, they develop the specialized tools required for their experiments.

Knowing what you need and figuring out how to modify equipment is part of the nature of research, said Hamza Balci, Ph.D., assistant professor of physics, whose laboratory provides a prime example of custom design. Balci looks at single DNA molecules and single proteins. He studies how the ends of chromosomes are protected against RPA, a protein specialized in detecting DNA damage in the form of single-stranded DNA.

DNA in the cell is in a double-stranded form and is separated into two strands when the DNA is copied (replication) or when one of the strands is damaged and needs to be repaired. In both cases, RPA binds to the single strands and stops the cell cycle until the replication or repair is done.

An exception to this system is the chromosome ends (telomeres), which naturally have a single-stranded overhang. Telomeric overhangs buffer the ends of chromosomes and allow cells to divide without losing genes. Binding of RPA to the overhang needs to be prevented to avoid a false signal and the disruption of the cell cycle. This is the focus of Balciãs study.

Building a System

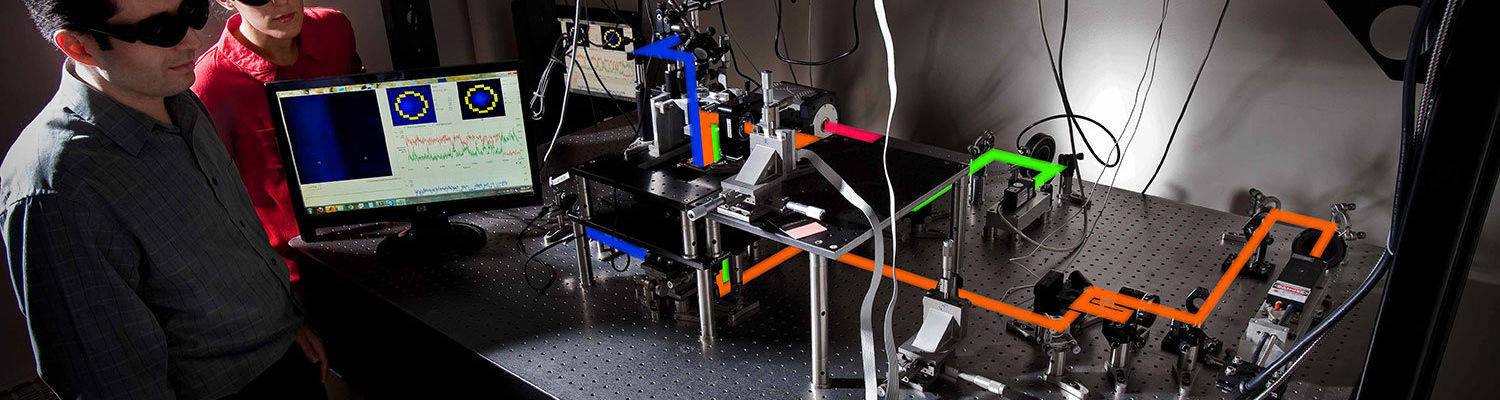

To do it he needs a microscopic imaging system that can image single DNA molecules and collect as much light as possible. The system requires a laser to penetrate only 100 nanometers from the surface ã not through the entire sample ã in order to reduce background noise.

The set-up is built part-by-part around an Olympus IX71 microscope. Balciãs research team has assembled lenses, mirrors, filters, dichroics and prisms in a configuration that guides the laserãs entry and exit path. An Andor Ixon EMCCD camera with single photon sensitivity is used to detect tiny signals.

The parts and the instruments are expensive and often can perform only one function where Balci needs several. The laser alone costs $15,000 new, although he found one for $2,000 on eBay. ãI use a lot of eBay parts,ã he said. Industrial companies that go out of business often sell their instruments there. Like other researchers, Balci used start-up funds from the university to help pay for the laboratory set-up. He also received a Farris Family Innovation Award for Young Investigators, a College of Arts and Sciences Research Resources award and a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

Essential to the lab were the services of the physics departmentãs technical shops, providing tools that could not be obtained commercially. Wade Aldhizer, research machinist specialist, built adapters for the microscope, including one that needed to be at a precise 11-degree angle. Alan R. Baldwin, Ph.D., research engineer in the electronics shop, made a customized controller box for the laser.

A Collaborative Approach

Balci, an experimental physicist who has been at ê§Ååè¨öÓØ¿ for five years, earned his Ph.D. at the University of Maryland in the field of superconductors. He learned optics and biophysics as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Illinois, where he had to build his own instrument set-ups to analyze data.

He collaborates with biochemists at ê§Ååè¨öÓØ¿ and sends his own graduate students to train with other research collaborators at the University of North Carolina, the University of California at Berkeley, and the University of Illinois Part of what they bring back is the ability to customize his lab for their own research projects.

ãYou can modify it,ã he says of the lab. ãItãs an open-frame structure.ã